Last year, a museum dedicated to the work of Étienne Terrus revealed most of its paintings were probably not by him. How did they get there?

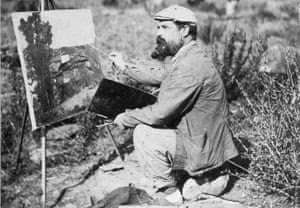

The real deal: artist Étienne Terrus, a friend of Matisse. Photograph: the Commune of Elne

Odette Traby was dying. It was the summer of 2016 and the sun baked the terracotta roofs of her hometown, Elne, in the south of France, as she lay in bed. Weeks earlier, the 78-year-old had been diagnosed with stage IV cancer. This grande dame of Elne town life had refused all treatment and chosen to tough it out alone. “She was someone who wanted to grapple with, to face up to, death,” says Dani Delay, her niece.

Traby had one consolation. She had spent the previous months trying to secure the future of her life’s work, the town’s art museum. It was dedicated to the work of the local artist Étienne Terrus (1857-1922), a friend of Henri Matisse who had been largely forgotten by the time Traby established the museum in the mid-90s. When nearly 60 Terruses came on to the market in 2015, Traby rallied two local historical associations to raise tens of thousands of euros, securing at least 30 of the works. As her life ebbed, at least Traby could tell herself that her beloved museum was closer to gaining the “Musée de France” status that would give it priority state funding and resources.

There was just one problem. On 27 April 2018, more than 18 months after Traby’s death, Elne’s mayor stood at the inauguration of the renovated Musée Terrus and announced to the public that nearly 60% of its collection was fake. The mayor, Yves Barniol, had known for months; 82 works out of a total of 140, worth approximately €160,000 (£140,000), had already been seized by the gendarmerie in nearby Perpignan. Barniol was soon fielding calls from the New York Times, the BBC, Al Jazeera and the Japan Times. Despite the embarrassment, he felt it was better to come clean. “It’s hard. It’s a shock,” he tells me later. “But 60,000 people have seen these fakes over the last 15 years – that’s unforgivable.”

The Terrus affair represents a new kind of art crime, driven by what one French radio station has called “low-cost fakes”. As it has become harder for forgers to penetrate the top tiers of a global art market saturated with counterfeits – a figure of as many as 50% is often cited – they are thought to have turned to lesser works. Prior to the scandal, a genuine Terrus was not exorbitant, selling for up to €6,000. We now live in a broader culture of inauthenticity – “deepfake” Barack Obama videos, Russian troll factories – but many of the alleged Terrus fakes were sloppy. Why had the experts, whose job it was to prevent this from happening, failed so badly? If Traby loved Terrus so much, how could she not have spotted them? How much did the people around her know? And who painted the fakes that entered the museum with such distressing ease?

***

I take a stroll around Elne on the first day of June 2018. It is a calm huddle of 8,500 people who live around a fortified hill, nine miles north of the Spanish border in the Pyrenées-Orientales département; Hannibal pitched camp here when it went by the name Illiberis and was the regional capital. The blue-gabled house where Terrus’s descendants still live is next to the ramparts in the lower section of town. In the tourist office, I am warned that, due to an obscure feud, the family refuse to discuss the artist. When I ring their bell, a long-faced pensioner behind the gate swats me away: “Non!”

Eric Forcada, the art historian who uncovered the fraud, lives eight miles away in Perpignan. Sitting at a table in an art deco cafe, he wears his politics on his breast – a yellow Catalan ribbon – and his trainers, the yellow-and-red senyera stripes. The 43-year-old smiles wryly as he explains his involvement. After Traby’s death, he was chosen by the Elne municipality to oversee the renovation of Musée Terrus, making it ready to display the new works. As soon as he received images of them, at the end of August 2017, he knew something was wrong: “I said to myself, it’s not possible.”

There was barely any stylistic consistency among the new works. A lot were crude, “holiday-club” stuff – not consistent with the work of the charged colourist who had captivated Matisse. Terrus spurned a Parisian academy education to paint nature in his backyard, the vigour and heat that ran through his work rooted in a strong Catalan identity.

Further investigation into the museum’s collection revealed more anomalies. On one painting, the signature came off when Forcada brushed it with a gloved hand. Another had been signed twice: Terrus and J Armengol. There were watercolours on perfect white paper that didn’t look a century old, with a tight industrial weft commonly available only after the second world war.

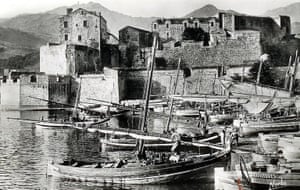

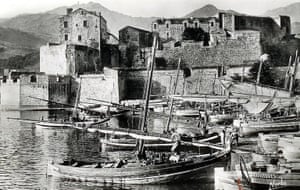

Most flagrant seemed to be the case of two oil paintings featuring the Château Royal at Collioure, the port a few miles south where Matisse jointlyestablished fauvism, the movement that sounded the fanfare of modern art. The paintings featured a flat-roofed tower on the castle that had been renovated that way in 1957; by then, Terrus had been dead for 35 years.

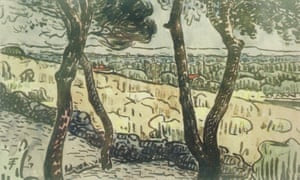

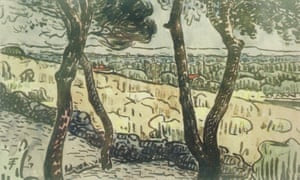

An alleged forgery in the Musée Terrus collection…

…and Terrus’s original. Photograph: courtesy of Montfreid private collection

Backed up by three other specialists, Forcada explained his findings at a meeting of the two associations that had funded their purchase; his views were later corroborated by another expert, who must remain anonymous under the terms of an ongoing police investigation. “People were shocked,” says Forcada. “How could they have been fooled when they did everything in good faith?”

He soon realised he had stirred a hornets’ nest. The day the public announcement was made, he started receiving calls from private collectors, who wanted him to verify their works by Terrus – and other artists. It became clear that the art market in Roussillon – the wider region containing Pyrenées-Orientales – was “gangrenous”; Forcada estimates there are hundreds of forgeries in circulation, among them 200 to 300 Terruses, worth as much as €1m.

Most of these fakes are in private hands, but they sometimes end up in museums when they are lent for exhibitions. In May 2018, weeks after Forcada’s discovery came to light, the Musée Rigaud, Perpignan’s main art museum, allegedly withdrew two suspect paintings by Terrus’s contemporary Augustin Hanicotte, lent by a private collector. Its director, Claire Muchir, later denied the works had been included in the exhibition, but one had featured on early publicity material. Another national museum, the Museum of Modern Art in Céret, 14 miles south-west of Elne, is putting a large collection it has just been bequeathed under close scrutiny to avoid such embarrassment; Forcada, who has seen the works, believes 5% are “doubtful”.

Forcada thinks the forgers exploited the intensity of the Roussillon art market, with its mania for local artists. Many of this group were relatively little-known; their works were not valuable enough to be subject to the kind of scrutiny a Pablo Picasso, say, would undergo before auction. Surrounding the giants who came to work here in the 20th century’s first decade – while Matisse and André Derain invented fauvism at Collioure, Picasso and Georges Braques workshopped cubism in the mountains at Céret – was a tight-knit hub of locals, including Terrus, Hanicotte, Aristide Maillol, Gustave Fayet, George-Daniel de Monfreid and Madeleine Arnaud.

A dapper gent in a pink blazer walks over to the cafe where we are talking and chips into our conversation. He is Michel Sitja, the director of the office of Perpignan’s mayor. A collector himself, he has organised exhibitions and says he understands the local mentality. “Often people buy a painting because it shows a bit of their village, not necessarily because of who painted it,” he says. This, Forcada says, has translated into a “narcissism” susceptible to exploitation – particularly if, like Odette Traby, you are in a position to set up a museum.

***

“I’m the only one to bear her name,” says Frédéric Traby, Odette’s nephew. “Every time I introduce myself, I have to say, yes, she was my aunt. And they always say, ‘Oooh, what a character!’” Weeks later, he and I are in a Perpignan lawyer’s office with his cousin Delay. They are her closest living relatives (she had no children) and have never talked to the press before.

They tell me about the force of nature who was their aunt: “She was a militant, passionate in everything she did,” says Frédéric. She had been a biology teacher, a trade unionist, five times a cultural adjunct and the founder of a Catalan music festival, as well as the town’s first girls’ basketball team. But she could be brusque and authoritarian. The social club she founded for Elne’s art aficionados was named Le Cercle des Authentiques Cabochards (“The Circle of Old Gits”). With her austere dress sense, she had the air of someone dedicated monastically to higher things. Perhaps she saw in Terrus, regarded in his time as a wild “bear” with no time for bourgeois propriety, a fellow iconoclast. She took up his cause with complete dedication.

Traby set up Musée Terrus with her long-term partner, Michel Briqueu. After his death in 1994, she became the leading authority on the artist. Annie Pézin, who succeeded Traby as Elne’s cultural adjunct in 2008, deferred to her on matters relating to Terrus, perhaps calamitously in the case of the town hall’s 2013 acquisition of 16 Terruses, now also in police hands. “You have to understand it in the context of the town, which isn’t big. And her strong personality,” says Pézin, a small, alert woman squinting uneasily through heavy-rimmed glasses over a picnic table in her garden. Traby rarely doubted her own mind, agrees Nicolas Garcia, Barniol’s predecessor as mayor, who fenced with her over the price of acquisitions. “‘You don’t haggle over art like a carpet,’ she’d say.”

Is it real or is it fake? In this painting of the Château Royal at Collioure, the tower roof is flat…

…but in Terrus’s lifetime, it sloped. Photograph: the Commune of Elne

No one I speak to questions Traby’s integrity. But after Barniol and his rightwing administration was voted into office in early 2014, she pushed harder for acquisitions – fearful of losing her influence over the museum. She had started to lose sight in one eye, possibly leaving her less able to spot red flags in the new acquisitions. “The only thing she’s guilty of is believing too much,” says Frédéric. “Of having believed she knew enough, when in the end she was cheated.”

***

I decide to dig into the provenance of the Terruses. The vast majority were acquired by the museum’s steering body, the Terrus committee, which consisted of Traby; Gérard Rouquié and Alain Lesage, two Perpignan art dealers; and a twentysomething intern who is now in ill-health. Lesage sold the artworks, acquired over many years, to the museum. Rouquié – a well-known figure in the Roussillon art-dealing world – authenticated them.

By July 2018, three months after Barniol’s revelation, the Musée Terrus case has passed en instruction – a higher tier of investigation led by an examining magistrate reserved for more serious crimes, often involving an organised ring. The mood is tense. A few weeks earlier, Forcada was interviewed by the police for five and a half hours, to see if he had any vested interests in outing the Elne fakes. The case isn’t moving as fast as he had hoped.

I find Rouquié and Lesage’s peach-fronted shop in a poky square round the corner from the cathedral. No one answers the bell. I peer up the three-storey facade; latticed shutters have been drawn halfway down the windows. Someone taps me on the shoulder. It is the waiter from the cafe opposite, who has seen me snooping: “They’re always up there looking out. They can see you, but you can’t see them.”

Finally, Rouquié comes to the door. Wearing jogging bottoms and a T-shirt emblazoned with the word “London”, the wiry 79-year-old rocks on his heels in his doorway. What does he, as the authenticating expert, make of the declaration of the Elne paintings as fake? “La montagne accouche d’une souris,” he says (“They’ve made a mountain out of a molehill”). “There are maybe some doubts about 10% of the collection, but I don’t know where they’re getting 60% from.” He retired as an active dealer in 2001 and installed Lesage, his business partner, to replace him. The police still haven’t formally interviewed him, he tells me, but they have seized documents related to his work on the Terrus committee.

When we meet again a few months later, Rouquié tells me he met Traby for the first time in the mid-00s when she saw a watercolour by Terrus in his window. After they supplied her with more Terruses, she invited Rouquié and Lesage on to the museum committee. Although he issued the certificates of authenticity as a formality, it was Traby who made the real decisions, he says. (The intern on the committee later tells me Rouquié had much more sway than this.)

Eric Forcada, the art historian who uncovered the fraud. Photograph: Samuel Aranda/Panos/The Guardian

The committee had little expertise in Terrus’s work: Rouquié was the only member with any relevant qualifications. He says he saw no conflict of interest in authenticating the paintings sold by his partner: “It’s totally normal, within the rules. In Paris, there are plenty of people on committees who buy and sell.” (A British expert tells me it is true that the French system is far more laissez-faire.) Regarding the improbable stylistic variation among the works, Rouquié argues that Terrus “did a bit of everything”. He claims the industrial watercolour paper dates back to 1880, and that in certain circumstances it can weather decades unscathed.

What about the tower anachronism? “The painter paints what he sees, but also what he imagines. All the greatest painters did it. If I say: ‘When Terrus painted it, he decided to give it a different roof,’ who can prove the contrary?” But the precise roof that was built 40 years later on the same tower? Rouquié grinds his teeth. “All this saying, ‘He couldn’t have imagined a roof,’ it’s totally idiotic. As an expert in Terrus, I can say that’s how he did things.”

The works offered to the two associations, he says, came from four sources, including two “wheeler-dealers” who had supplied him for many years, and a court bailiff auction that furnished a single oil painting. But most came from a “Monsieur X”, a former estate agent who lives in the region. Rouquié and Monsieur X only completed the transactions in April 2018, when Rouquié insisted he write him a formal receipt (now with the police). Rouquié claims he paid Monsieur X with luxury watches worth €25,000 and “thousands” in cash – not unusual for traders and collectors who want to avoid tax audits.

He reiterates the details, reading off the deposition he has prepared for the gendarmerie. But instead of referring to Monsieur X, as he has throughout our interview, he lets slip a name: Monsieur Amiel. I have no idea if he has done it deliberately or not, but I note it down.

***

“He’s fucked us all!” says Franck Amiel, bounding around his living room, when I repeat Rouquié’s version of events. “If I see him, I’ll smash his face in.” Two spaniels yelp and bounce up and down near the windows, riffing off their owner’s nervous energy. Amiel lives in a cavernous mansion in the village of St Paul de Fenouillet, about 20 miles west of Perpignan. He admits selling his collection to Lesage in 2016, but says it contained no Terruses. He says he is a victim in this scenario. He walks me up his staircase, pointing out several supposed fakes by local artists, some of the many artworks and antiques he says Rouquié has sold him since 2000.

Is Amiel a perpetrator or a patsy? Forcada has declined to evaluate artwork shown to him by Amiel, because the estate agent’s role in the affair is “not clear”. Rouquié showed me his livre de police, a record book he is legally obliged to keep, detailing two batches of Terruses purchased from Amiel in October 2012 and May 2013. They were not among the 30-odd works that ended up in the museum through the Elne associations; Rouquié told me those sales took place off the books. But, he says, the October 2012 entry, for 16 works obtained from Amiel, corresponds to the sale signed off at Elne municipality in 2013 – the paintings that hung in the town hall. Rouquié steadfastly denies that he and Lesage knowingly acquired fakes from Amiel.

If Amiel was the source of many of the paintings offered to the two associations, where did he get them? What was the origin of the other works that found their way into the museum collection, some as far back as 15 years ago? What of the 1,000 fakes believed to be in private hands?

Forcada’s hunch is that the Roussillon forgery network is split into two parts: one targeting the museums and bourgeois clients, another the more informal street markets and regional auction houses. Several antiques dealers I speak to claim that organised criminal networks often play a role in introducing China-produced fakes, which turn up at salons, flea markets and auction houses across France. Throughout my research, one name keeps cropping up: that of a local trader. Rouquié’s record book confirms that this mystery man is a supplier, one of the wheeler-dealers he mentioned in our first interview. A former police officer reveals that the man has sold forgeries to auction houses in Pyrenées-Orientales, possibly with their collusion. Auction houses pay by cheque, so the sales are documented but confidential.

Terrus (seated) with his friend Matisse (standing). Photograph: the Commune of Elne

Later, Rouquié talks me through the suppliers of most of the paintings offered to Elne’s two associations, and of other alleged fakes. There are striking correspondences: the majority of the supposed acquisitions from the local wheeler-dealer either closely resemble authentic Terruses, or seem to have been copied from old postcards in the museum’s 2002 catalogue. Could they be the work of a dedicated forger, as opposed to a hotchpotch by other artists later re-signed Terrus? Forcada believes there may be several forgers working under a kingpin, someone “elusive, remote and mysterious”, as he puts it. But even if the local wheeler dealer is the mastermind, the ex-cop warns me against pursuing him: “It could finish badly for you. He’s got nothing to lose.”

***

January 2019. People turn up at the Musée Terrus asking to see the fakes, but the police still have them. Visitor numbers are down. No one has been charged. The magistrate who led the investigation for six months has gone on sabbatical and been replaced by someone else, who has since left for unexplained reasons, leaving no one in charge.

Rouquié receives me again in his office, recovering from a stomach operation made necessary by the pressure, he says. He still insists that most of the seized works are genuine. I don’t know if he is lying, telling the truth or a cloudy cocktail of the two – that he convinced himself the paintings were by Terrus and let Traby take the responsibility. Meanwhile, Amiel refuses all requests for follow-up interviews and has put his house up for sale.

Forcada is impatient but resolute. Some people believe the historian’s Catalan allegiances have led him to hold Terrus in too high regard, and to overestimate the number of fakes in circulation. It is clear a lot of the alleged forgeries are leaden and pedantic; but in Paris a collector shows me a genuine Terrus, a watercolour that is nearly as uninspired. The artist did have his off-days.

Forcada is calling for a clean-up of the market led by state museums – for example, by offering their expertise to private collectors. He believes the market could face an even greater crisis in a few decades’ time when the current generation of collectors dies and their fakes go up for sale. Ultimately, he wants to encourage a change of philosophy among collectors. “We have to get everyone on the same page, so we’re not drawn necessarily to fetishising a single work for its value, but to understanding the overall worth of an artist’s life.”

One person would have agreed. Once her work upholding Terrus was done, Traby organised her death with the same singlemindedness. She finally agreed to go into a palliative clinic – because of the pain, but also to give a prying neighbour the slip. She died on 4 August 2016, a year before Forcada blew things open. Only 10 people went to her funeral. Her niece and nephew, Delay and Frédéric, had been sworn to secrecy, even from other family members: their aunt didn’t want Elne’s professional mourners there, “crying crocodile tears”. There were no speeches; just a friend, with whom Traby had founded her music festival, playing the flute. “She was the master of ceremonies until her final moments,” says Frédéric. “There are very few people like that: ‘It’s my life from A to Z and it’s me who decides.’”

She bequeathed 13 Terruses to the museum, authenticated by Rouquié, which are now in the possession of the police. In her will, Traby asked for a room in Musée Terrus to take her name. She may not be remembered for the reasons she wanted, but hanging there are 19 paintings that speak for her undying love of art and truth.

• If you would like a comment on this piece to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).